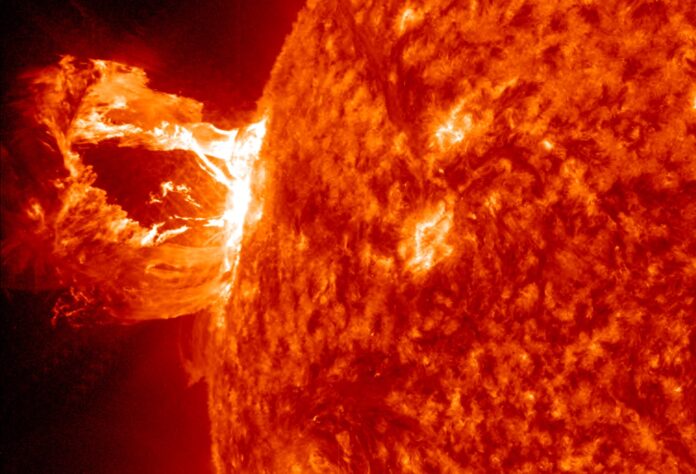

ST. ANDREWS, SCOTLAND — We may need to change how we think about the Sun’s biggest explosions. A recent study says that particles in solar flares can get as hot as 108 million degrees Fahrenheit (60 million degrees Celsius), which is almost six times hotter than what scientists thought before. This discovery, which has big effects on predicting space weather, helps to address a problem that solar physicists have been trying to figure out for decades.

Dr. Alexander Russell from the University of St. Andrews led the research that goes against the long-held belief that the ions and electrons in a solar flare’s plasma heat up to the same temperature. Dr. Russell and his team used computer models and experiments on magnetic reconnection, the main process that makes these flares happen, to figure out that electrons can become as hot as 10–15 million degrees Celsius and ions can go even hotter, over 60 million degrees.

This big difference in temperature is important because it takes ions and electrons a few minutes to exchange heat. The super-hot ions stay around long enough to change the brightness that the flare gives off during this time. The “spectral lines” of elements in the flare’s light get wider because these ultra-hot ions move so quickly. This is why these lines have always seemed larger and blurrier than what theoretical models said they would. It finally solves an astrophysics riddle that has been around since the 1970s.

We can no longer predict space weather as well as we could before since we now know that flare ions carry much more heat than we imagined. Current models, which assume that all particles have the same temperature, may be seriously underestimating how much energy a solar storm really has. The authors of the study suggest that future predictions use a “multi-temperature” method, which means addressing electrons and ions individually. This could result in more precise alerts for satellite operators, airlines, and astronauts, affording them additional time to prepare for potentially dangerous solar occurrences that can interfere with communications, damage satellites, and endanger space travelers.

The researchers are hopeful that future satellite missions would be able to directly detect the ion temperatures in flares. This would give them direct observational evidence to test this innovative and paradigm-shifting idea even more.