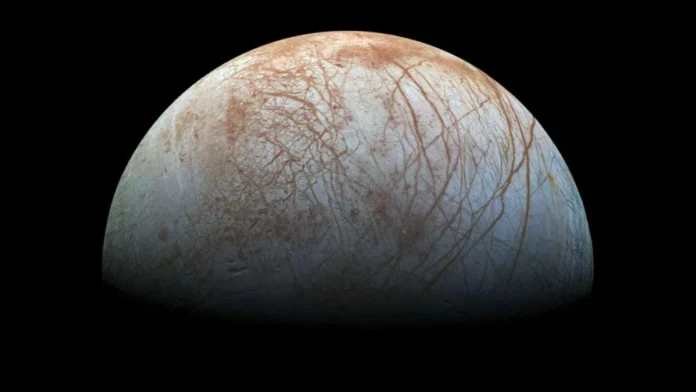

Heavy, power-hungry drills have long posed a major obstacle to probing the mysterious subsurface oceans beneath icy moons like Jupiter’s Europa and Saturn’s Enceladus. But a team of scientists from Technische Universität Dresden (TU Dresden) in Germany has proposed an innovative solution — a laser-based ice drill that could change how humanity explores these frozen worlds.

Their findings, published in the journal Acta Astronautica, outline a compact, energy-efficient drilling system that uses high-powered lasers to sublimate (vaporise) ice. By doing so, it eliminates the need for massive drilling machinery and cumbersome power cables, both of which are impractical for space missions.

Laser Drill Design: How It Works

The TU Dresden team’s laser drill design centres on using focused laser beams to vaporise ice directly. Instead of physically cutting or melting through layers of ice, the laser creates narrow, deep bores by heating small sections of ice until they sublimate — turning directly from solid to gas.

Unlike traditional mechanical or thermal drills that require heavy rods and continuous power, this surface-based system keeps all the key equipment on top of the ice. The vaporised ice gas escapes upward through the borehole and can be collected for chemical analysis, offering real-time insights into the composition of the subsurface environment.

Lead author Martin Koßagk explains that this method “enables deep, narrow and energy-efficient access to ice without increasing instrument mass,” making it ideal for missions constrained by spacecraft weight and energy limits.

Advantages Over Traditional Drilling Systems

One of the most promising aspects of the laser drill is its efficiency and speed. The laser vaporises only a tiny section of ice at a time, consuming far less power than a melting probe or mechanical drill.

In laboratory experiments and field trials in icy environments such as the Alps and the Arctic, the prototype demonstrated the ability to penetrate over a meter of ice, cutting through even dusty and layered formations faster than traditional systems.

Researchers observed that the laser could maintain its drilling performance with minimal power loss, making it a potential game-changer for future planetary exploration missions.

Implications for Future Space Missions

The laser ice drill could play a crucial role in upcoming missions to Europa, Enceladus, and even Mars, where scientists suspect that liquid water may exist beneath thick ice crusts — potentially harbouring microbial life.

Current mission concepts, such as NASA’s Europa Clipper and future Enceladus Orbilander, face the challenge of limited payload and power availability. TU Dresden’s laser drill could provide a low-mass, low-energy alternative for accessing subsurface environments and collecting pristine samples for astrobiological analysis.

Koßagk adds, “This approach makes subsurface exploration of icy moons more realistic,” underscoring the potential for in-situ resource investigation and life detection studies on distant worlds.

A Step Toward Unlocking Extraterrestrial Oceans

While still in its early stages, the laser drill prototype marks a major leap toward practical subsurface exploration technology. If successfully adapted for space missions, it could one day pierce the ice shells of Europa or Enceladus, opening access to their hidden oceans — some of the most promising places in the Solar System to search for extraterrestrial life.